This woman appears twice in the Gospels: once in

Matthew, and in today's reading from

Mark. I've preached on the Matthew version, so I'm posting that homily.

I

love this woman. She's the

only person in the Gospels who argues with Jesus and wins, who gets him to change his mind. She's my hero.

A few years ago, I took a two-week summer course on the Gospels at

GTU. The teacher was brilliant, but pretty unbearable. The class met four hours a day: his teaching style was to lecture the whole time. He only wanted to take questions or comments during breaks. About four of us -- two men and two women -- kept stubbornly raising our hands, and when he refused to let us talk, we started just calling out whatever we had to say. This clearly annoyed him no end, but we did it anyway.

One day we were doing a comparison of the Mark and Matthew passages about this woman. In Matthew, she's much more aggressive: the story happens outside rather than in a house, and she chases after Jesus and heckles him, like some crazy street lady. The teacher's point was that the Matthew version makes her ruder and less sympathetic so that Jesus' final acceptance of her will be more impressive: he's blessing this woman his audience would have despised.

During the break, I approached him and said, "Okay, she's ruder in the Matthew version, but how can she

ever be unsympathetic? She's begging for healing for her sick child. She's desperate. How could anyone not sympathize with that?"

The teacher looked at me, sniffed, sneered, and said, "Well, Susan, I'm sure

you don't have any trouble with obnoxious women."

*cough, cough*

No, sir. Only with obnoxious men.

On another, more serious note: I'm intensely grateful that I don't actually have to preach today, because I'm not sure how I'd tie this Gospel in with 9/11. I'd talk about Others in desperate need and compassion and healing, I guess. I'll be interested to hear what our preacher says this morning.

Last year, I preached on 9/11 and Katrina, on 9/11 itself. I may post that homily tomorrow.

Today

is one of my ministry-marathon days, though: church this morning, my monthly nursing-home service in the afternoon, and then it's off to the hospital for my first Sunday shift. Wish me luck!

And without further ado, the homily.

* * *

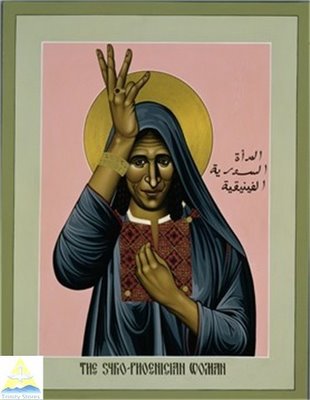

This is the woman we heard about in today’s Gospel. This icon was painted by Robert Lentz, and I find it profoundly moving. Look at her face, her downturned eyes and furrowed forehead. Look at the weariness and worry in that face. It’s the face of someone who’s so frantic about her sick child that she’s willing to chase down strangers in the street to demand help. It’s a face many of us might prefer not to look at, because there’s too much pain there, too much fierceness. It’s the face of someone who won’t take no for an answer.

It’s important for this woman to have a face, because we never learn her name. Not here in Matthew and not in Mark, where the other version of her story appears. In Matthew she’s the Canaanite woman; in Mark, she’s the Syro-Phoenician woman. We know her only by her label, her nationality, her otherness. She’s an outsider.

She’s an outsider to Jesus and the disciples because she’s not one of them. She’s a Gentile, not a Jew. In other circumstances,

she probably wouldn’t have wanted to have anything to do with

them, either. After all,

they’re the strangers here. They’re the ones who’ve just traveled from Galilee to the “district of Tyre and Sidon.” But she’s desperate, because she’s already tried everything her own district has to offer. She’s spent all of her money on useless priests and doctors. She’s become marked with the stigma of her daughter’s demonic possession: her neighbors won’t talk to her anymore. They shake their heads and cross the street when they see her coming; they make signs in the air to ward off the evil she carries. She’s an outsider even in her own homeland now, and she’s heard amazing things about this healer from Galilee. So she chases him. “Have mercy on me, Lord, Son of David!”

Jesus ignores her. Jews weren’t supposed to associate with Canaanites, who worshipped idols. Five chapters earlier in Matthew, Jesus specifically instructed his disciples, “Go nowhere among the Gentiles . . . but go rather to

the lost sheep of the house of Israel.” That’s the same phrase he uses in this morning’s reading. By calling Jesus “Son of David,” then, this frantic mother has committed a tactical error: she’s reminded him that he’s a Jew, and that she isn’t. But Jesus is her daughter’s last chance. So she kneels in front of him, the stones of the street cutting into her knees, and utters the oldest and most universal prayer of all: “Lord, help me.”

And Jesus -- the loving, the merciful, the compassionate -- Jesus the Son of God and Lord of Love, says to her, “It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.”

This is one of the most difficult moments in the Gospels. Jesus is our friend. We love him. He loves us. He loves everybody: lepers, tax collectors, women caught in adultery. And here he is, saying one of the cruellest things that anyone could tell a frantic parent. “

Our children are more important than

your child. Your child isn’t even human. Your child is a dog.”

There’s no way to whitewash this. If it doesn’t make you gasp with astonishment and rage, you aren’t listening. If we need any proof that the Son of God is also the Son of Man -- that Jesus is indeed fully and completely human -- here it is, because Jesus is being a jerk. I always picture his own mother, whenever she heard this story, shaking him by the shoulders and saying, “Jesus, I raised you better than that! What in the world were you

thinking?”

We don’t know what he was thinking, but we can guess. He’s just come from Galilee, where he was beset by crowds yammering for his help. To get away from them, he had to withdraw in a boat, and then he had to withdraw onto a mountain, and then he got into a nasty dispute about Mosaic purity laws with the Pharisees, who were powerful and potentially dangerous. Because Jesus is fully human, it’s a safe bet that right now, he’s fed up with crowds and utterly sick of people chasing him. He left Galilee to get away from all of that. He’s on vacation. These people aren’t his job. He just wants to be left alone for a while. And because he’s offended the Pharisees, who accused him and his followers of unholy behavior, he may be feeling a little defensive about his own religious credentials. The Law says not to mingle with Canaanites? Fine, then. He’s just obeying the Law. He’s being a good Jew.

The Canaanite woman knows better. She knows that her beloved daughter isn’t a dog, but she’s not going to argue the point. She’s already made one tactical error, and she can’t afford a second, not while her child remains in torment. Instead, she uses Jesus’ own metaphor against him. “Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table.” She’s reminding him, quite pointedly, that God takes care of dogs, too. She doesn’t need much: a crumb will do. What kind of God would withhold crumbs, even from a dog?

This woman may not be Jewish, but she has plenty of

chutzpah. She’s the New Testament version of Jacob, wrestling with the angel and saying, “I will not let you go until you bless me.” She’s talking back to God, holding God accountable: even though she’s not Jewish, even though her own friends and neighbors cross the street to avoid her. Even though she’s a nobody.

And Jesus hears her. He comes to with a start and remembers who and what he is. He may be the Son of Man -- fully human, sick of crowds and craving solitude -- but he’s also the Son of God. He doesn’t get to take vacations from that job, any more than the woman kneeling in front of him gets to take vacations from the job of caring for her sick daughter. And so he does the right thing, finally, and blesses her. “Woman, great is your faith! Let it be done for you as you wish.” And her daughter is healed instantly.

What is this mother’s faith, exactly? In God, yes, in the fact that even a crumb of God’s love will heal her daughter. But -- even more profoundly, I think -- she also has faith in her own worthiness, even in the face of repeated rejection. She and her daughter are people. They’re not dogs. They’re not nobodies. The Canaanite woman has faith in the fact that she deserves God’s love as much as anyone else does, and she has faith in the fact that if she says so, God will listen, even if it takes a few tries to get through. This nameless woman teaches us that persistence is a form of prayer. She teaches us that talking back to God isn’t always a sin. Sometimes, when you’re acting out of love and faith and not just out of anger, talking back to God is what you have to do to get the blessing you need. Sometimes God needs to be reminded what God’s job is.

She must have looked a lot happier than this, after her daughter was healed. Imagine her rushing through the streets back home, running away from Jesus as swiftly as she ran towards him before, because now she just wants to get back to her child to see if it’s true, to see if everything’s all right. And it is. Can you imagine her face then? Can you imagine her joy? Her face must have shone brighter than the sun, when she saw her daughter whole again.

But that’s not how Robert Lentz painted her. He painted her when she was still fierce, worried, demanding. He gave her this face because so many people wear this face still. It’s the face of all the people who wave picket signs and write petitions and organize protests. It’s the face of any parent who’s ever demanded justice and healing for children other people don’t want to acknowledge. It’s the face of anyone who’s ever insisted that the church open its doors more widely: to women, to ethnic and sexual minorities, to the poor and the disabled. It’s the face of everyone who knows that God’s job is love -- even when people are being jerks -- and who isn’t afraid to kneel down in the middle of the street to say so.

This woman doesn’t have one name. She has many. Her name is Rosa Parks, Sister Helen Prejean, Cindy Sheehan. Her name is yours, mine, our neighbor’s. It’s the name of anyone who’s ever held God accountable. It’s the name of anyone who’s ever chased God down and refused to take no for an answer.

Amen.